by Jennifer Bishop Jenkins

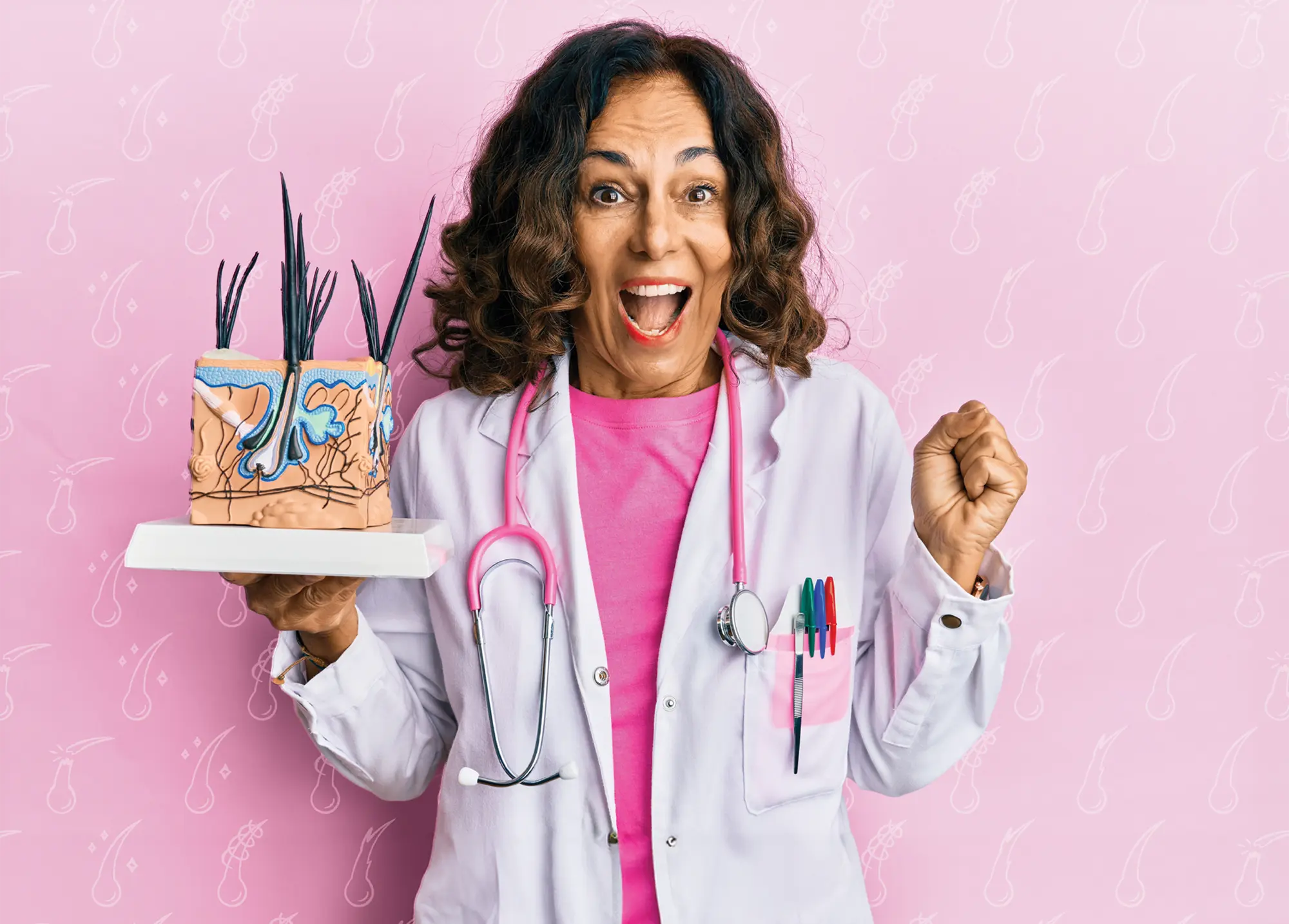

here are an estimated 900 million dogs in the world and most are double coated. Approximately 80%1 live without a home or owners and are called free ranging.2 They are all short- or medium-length double coats, and a large number of pet dogs are also double coated. All their fellow canids in the wild, such as foxes, coyotes and wolves, have a medium-length double coat, which is called the “natural” or “normal” category of canine coats by veterinary dermatology texts.3

here are an estimated 900 million dogs in the world and most are double coated. Approximately 80%1 live without a home or owners and are called free ranging.2 They are all short- or medium-length double coats, and a large number of pet dogs are also double coated. All their fellow canids in the wild, such as foxes, coyotes and wolves, have a medium-length double coat, which is called the “natural” or “normal” category of canine coats by veterinary dermatology texts.3

Had humans not spent millennia selectively changing dogs’ coats to serve other purposes, this would likely be the only coat type for dogs—but it is not. We have everything from Poodles to Bergamascos to Maltese to the American Hairless Terrier now.

A Language Problem

So why is defining this basic term “double coat” even an issue for us? To precisely define what the double coat is and how it works should be important to our industry, given its universality. Yet, this most common of all dog coats illustrates a language problem we struggle with, because the term “double coat,” like some other key vocabulary words for us, is not always used by groomers to refer to the same thing.

Our pet grooming industry is not only largely unregulated, but certification through extensive hands-on testing under the direction of a master (mandatory in other trade industries), is entirely voluntary for us. Our industry has, as a result, not yet acquired the standardization of curriculum and practice that other trades have. Such standardization leads to the creation of jargon—a mutually agreed upon common vocabulary of specialized terms used to speak about technical specifics, like the words that doctors and lawyers use when they speak to each other.

Sadly, it is the dogs that sometimes pay the price for this lack of agreement on basic concepts in dog grooming. However, the more we all work to educate ourselves by attending trade shows and online events, by reading researched publications and by talking with each other about this, the more we help to build that common understanding of words we all use.

Primary vs Secondary Hairs

The most common misunderstanding that I hear is that double coats apply to any coat type that has both primary and secondary hairs. These different hairs are also called topcoat, or guard hairs, and undercoat.

Mammals all have hairs of various kinds that are governed by genetics. Like our skin, hairs are made up of keratin proteins and are filament-like extensions of the skin composed of mostly dead cells. In mammals, all hairs and their follicles can have different shapes, pigments, lengths, sizes and textures.

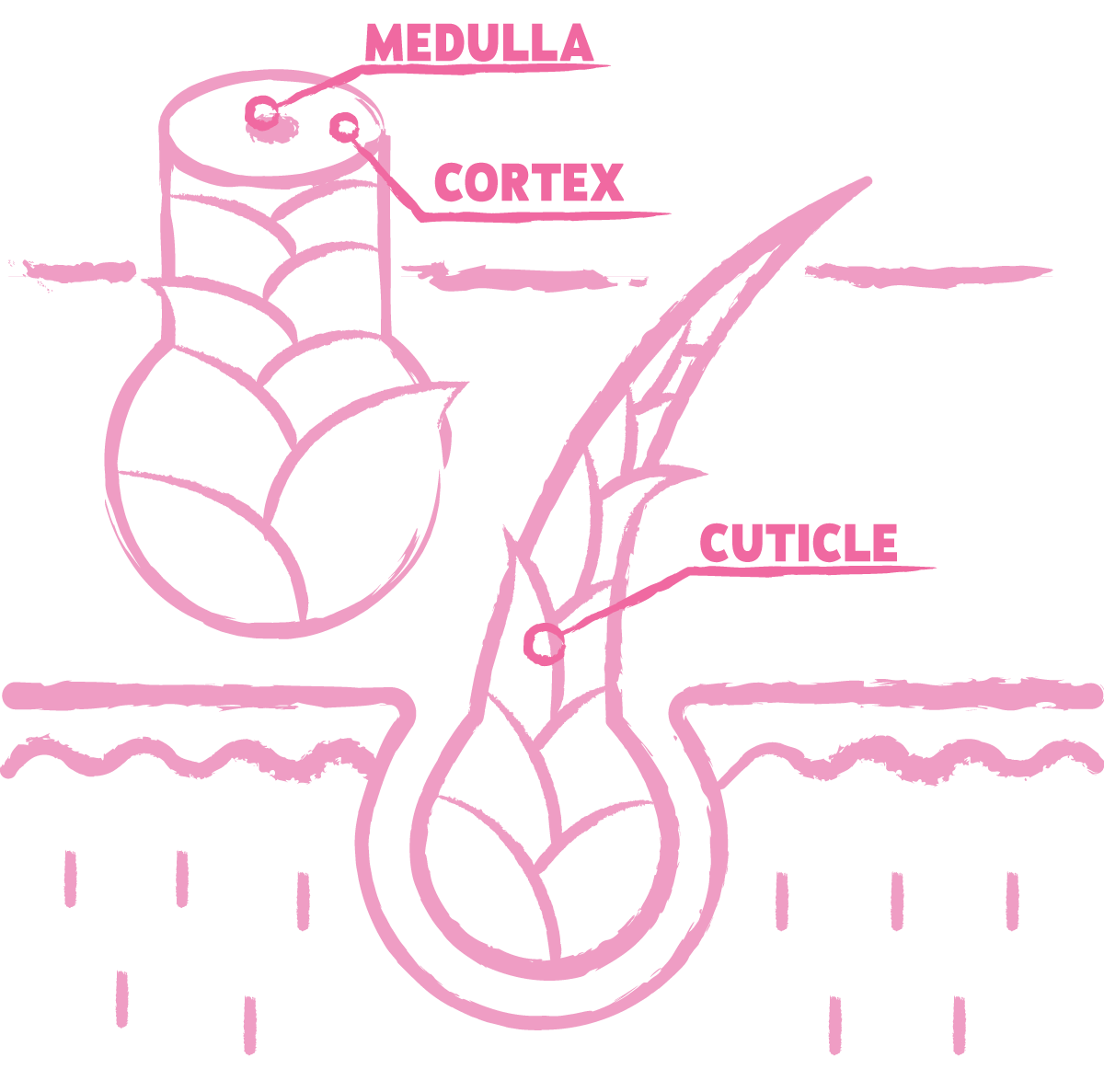

Anatomically, primary hairs have three layers. The scaly, outer protective part of the hair is the cuticle. The strong, stretchy, inner core of the hair is the medulla. And in between those two lies the middle layer of the hair, the cortex, which contains, among other things, hydration, pigment and nutrients. Primary hairs have all three of those layers. They are always longer, taller, more substantive, more weather resistant and more pigmented than secondary hairs, as well as longer lasting, often for years.

Secondary hairs lack a medulla. They are not fully formed hairs. They are temperature-regulating fuzz—a form of insulation that increases during the colder, shorter days, and falls out quickly when the days grow longer and warm up. They change their entire thickness twice a year prior to the solstices. They are always fuzzy, come in and fall out very quickly, and are not weather resistant or protective of the skin.

On a true double coat, the primary and secondary hairs are on an entirely different schedule and agenda and do not require much human interference. The primary hairs have a slow-growing or anagen growth phase, and a long dormancy in the telogen or resting phase, often for years. They come in and are meant to stay in order to provide structure and protection of dogs’ skin. The secondary hairs go from anagen to catagen to telogen and out very rapidly, several times a year. Their job is to regulate temperature.

This is why fur-type dogs can’t be cut or shaved. Only de-shedding should be done to assist in removing the undercoat as it sheds out naturally. If you shave a double coat a few times in their lives, they will likely never grow back their primary hairs, leaving only the undercoat to grow back. Skin cancer, among other things, is a danger if the primary hairs are removed. Our job as professional groomers is to remove seasonally shedding undercoat and protect the topcoat for its long-term job of skin protection.

A CLOSER LOOK

While it is understandable that some would feel the term “double coat” could apply to any dog’s coat that has both primary and secondary hairs, it is not a very helpful term for us to use simply because almost all dogs have primary and secondary hairs. So, if that were the definition of a double coat, we could not distinguish between the coats of a Labrador Retriever, a Shih Tzu, a Poodle and a Border Collie. Virtually every coat type except smooth coats like Boxers, Dobermans, and hairless breeds have both primary and secondary hairs. The double coat is more than just the presence of those two types of hairs.

Double-coated breeds have primary and secondary hairs, as most dog coats do, but what is unique to the double coat is the natural seasonal shedding cycle of a massive amount of undercoat. This is aligned to the seasons and triggered by the change in the length of light as winter and summer solstices approach.

On wolves in the wild we can observe tufts of undercoat blowing out on their own in the spring, making way for a summer coat that allows airflow to the skin while still reflecting dangerous sunlight away. This natural double coat largely cares for itself and works well without professional grooming. Of course, if you are living with an Australian Shepherd, a Newfoundland or a Samoyed—all true double coats of different lengths—professional grooming helps keep your home much cleaner.

Wire-coated breeds like many terriers do not seasonally blow out their secondary hairs the same way. Their coats require some pulling to help their shedding cycles because of their thicker skin, deeper follicles and more complex wire-textured protective hairs. The secondary hairs of Poodles and Shih Tzus may appear on our combs as we pull through their coats, but they do not shed out seasonally like a true double-coated dog would. In fact, in most hair-type, undetermined-length coats, the secondary hairs are almost as long as the primary hairs.

Defined in Biology

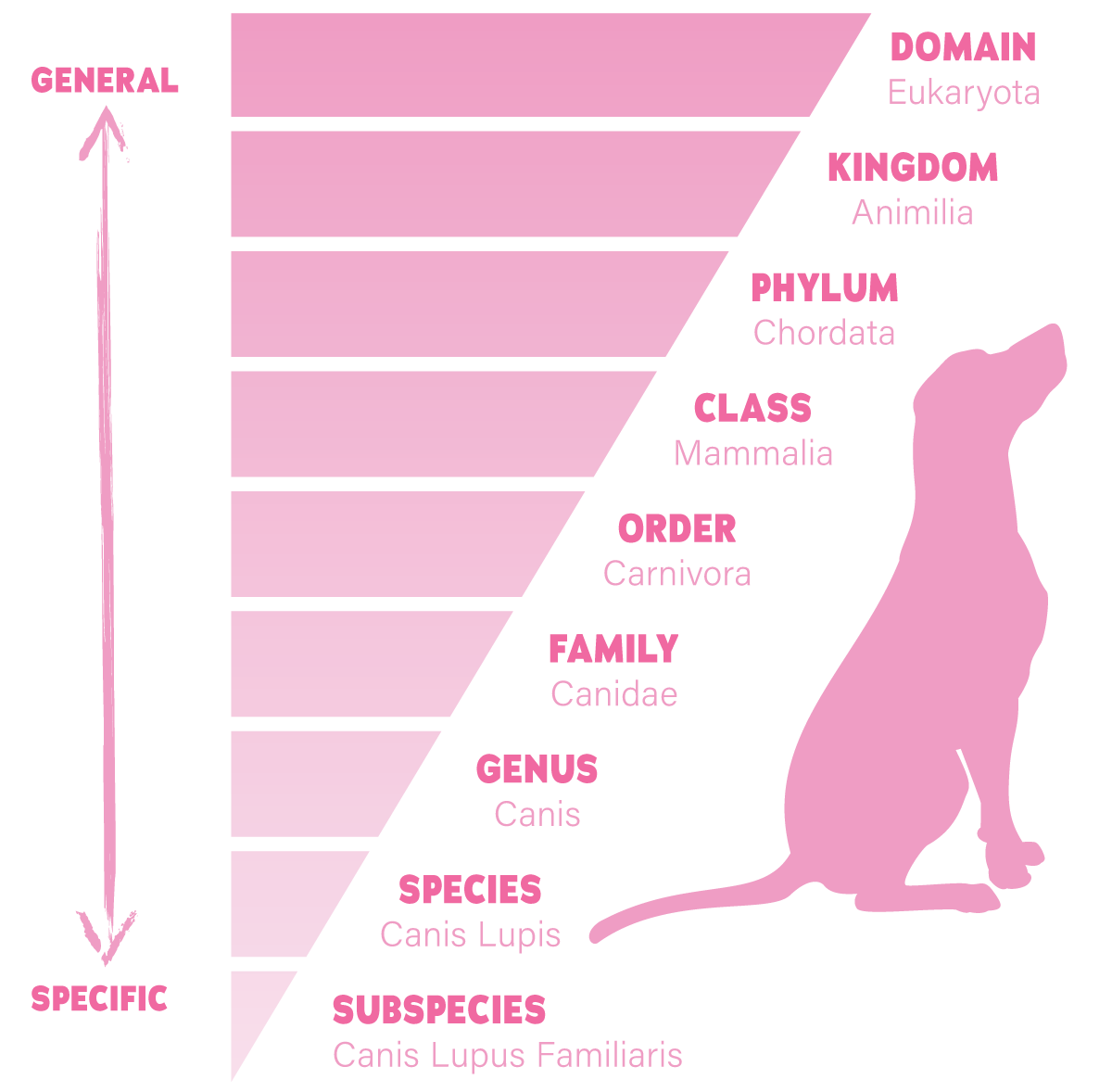

The best and most basic definition of anything biological is to look at that organism’s taxonomy, a term you may have heard in high school biology. Taxonomy is a scientific naming convention that systematically classifies all living organisms, from microbes to plants and animals.

Taxonomically, dogs are a multi-celled organism—clearly an animal, not a plant. Their phylum is Chordata, which means they are vertebrates. Their class is Mammalia, which means they have skin and hair, and are warm-blooded and nurse their young, like us Homo sapiens. The order level is where we split from them; they are carnivores and we are primates. Their family is Canidae, commonly referred to as canids. This includes foxes, coyotes, wolves, jackals, dingoes, dogs, etc. Their genus, species and variety is Canis lupus familiarus (meaning domesticated dog).

The most important way we groomers can define the double coat is to ground it in that scientific understanding of its biological makeup. The double coat is the natural coat of the entire Canidae family. The double coat is, by definition, what most canids have all over their bodies.

One reason why the dog is so diverse in appearance is because they have co-evolved with us for tens of thousands of years—the only two species on Earth known to co-evolve in this relational way. We humans live in diverse climates, hunting for diverse food sources, all over the planet. The most diverse single mammal species is the dog, developed both naturally and with some human help, over tens of thousands of years to be built for those specific places and those specific jobs.

While still very present, not just in the wild but in our homes, the many domesticated true double-coated breeds that are our beloved pets—from Labrador Retrievers and German Shepherds to the longer double coats of Shelties and Newfoundlands—we groomers still have a job to do for them. We can help remove the shedding secondary hairs for their weary families while protecting the vital primary hairs to keep their natural coats functioning throughout the year. And, since we already know when these coats will need the most care, we can schedule accordingly and be ready for them when shedding season arrives!

References:

- Lord, K., Feinstein, M., Smith, B., Coppinger, R. (2013). Variation in reproductive traits of members of the genus Canis with special attention to the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Behavioural Processes. 92: 131–142.

- Gompper, M. (2013). The dog–human–wildlife interface: assessing the scope of the problem. Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–54.

- Miller, W., Griffin, C., Campbell, K. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th Edition. Saunders.