t goes without saying that cat grooming is different than dog grooming. And while a lot of the differences are widely accepted, some of the most important differences in grooming cats are not obvious or even visible because they are anatomical, involving microscopic differences in cat skin and coat. Equipment and procedures that are fine for dog grooming are often not safe for cats.

t goes without saying that cat grooming is different than dog grooming. And while a lot of the differences are widely accepted, some of the most important differences in grooming cats are not obvious or even visible because they are anatomical, involving microscopic differences in cat skin and coat. Equipment and procedures that are fine for dog grooming are often not safe for cats.

The famous “Cat Daddy” and Animal Planet TV star, Jackson Galaxy, uses a perfect analogy to describe cat skin, cautioning us that it is “tissue-paper thin.” And veterinary science completely backs him up on that description. The thickness of a cat’s skin varies with species, breed and location, but ranges from 0.4 to 2 mm. In comparison, dogs’ skin thickness ranges from 0.5 to 5 mm. Even hairless cats, with their slightly thicker skin, still have microscopic vellus hairs to provide some protection. To underscore the severity of the thinness of their skin, cats can even get a unique condition called “skin fragility syndrome.”1

The answer, as with many complex questions, is “it depends.” No one is suggesting that heavily matted cats can be brushed out. They cannot. There are, however, other alternatives and mitigations that are much healthier for the cat than complete shave-downs or even the popular “lion cut.” A full shave of the torso of a cat is almost never necessary, and potentially unhealthy for the cat. It is especially wrong if it is being done unnecessarily. Other options include requiring more regularly scheduled grooms, teaching the owner to assist with home care, pre-soaking in conditioners, spot shaving, or even shaving certain areas like rear pantaloons or bellies that cats spend so much time sitting on. All of these are much better for the wellbeing of a cat than a shave of the full torso.

t goes without saying that cat grooming is different than dog grooming. And while a lot of the differences are widely accepted, some of the most important differences in grooming cats are not obvious or even visible because they are anatomical, involving microscopic differences in cat skin and coat. Equipment and procedures that are fine for dog grooming are often not safe for cats.

t goes without saying that cat grooming is different than dog grooming. And while a lot of the differences are widely accepted, some of the most important differences in grooming cats are not obvious or even visible because they are anatomical, involving microscopic differences in cat skin and coat. Equipment and procedures that are fine for dog grooming are often not safe for cats.

The famous “Cat Daddy” and Animal Planet TV star, Jackson Galaxy, uses a perfect analogy to describe cat skin, cautioning us that it is “tissue-paper thin.” And veterinary science completely backs him up on that description. The thickness of a cat’s skin varies with species, breed and location, but ranges from 0.4 to 2 mm. In comparison, dogs’ skin thickness ranges from 0.5 to 5 mm. Even hairless cats, with their slightly thicker skin, still have microscopic vellus hairs to provide some protection. To underscore the severity of the thinness of their skin, cats can even get a unique condition called “skin fragility syndrome.”1

The facts about cats’ dangerously thin skin and vitally protective and abundant fur coat raise questions about the practice of routine shaving of cats by pet groomers everywhere. So, should cats be shaved?

The answer, as with many complex questions, is “it depends.” No one is suggesting that heavily matted cats can be brushed out. They cannot. There are, however, other alternatives and mitigations that are much healthier for the cat than complete shave-downs or even the popular “lion cut.” A full shave of the torso of a cat is almost never necessary, and potentially unhealthy for the cat. It is especially wrong if it is being done unnecessarily. Other options include requiring more regularly scheduled grooms, teaching the owner to assist with home care, pre-soaking in conditioners, spot shaving, or even shaving certain areas like rear pantaloons or bellies that cats spend so much time sitting on. All of these are much better for the wellbeing of a cat than a shave of the full torso.

Yes, we need to take time with the owners to educate them so that they, too, can understand the vital role that hair and skin play in their cat’s health. We can stock and sell them the right combs and equipment to help maintain the coat. We can offer spot removal of mats while preserving what we can of their fur. At my salon, all the long-haired cats that we groom are mandated to be in for full or partial grooming on at least a two- or three-month schedule. The owners are happy to comply because this keeps the price down, their cats happier and healthier, and their homes cleaner of shedding.

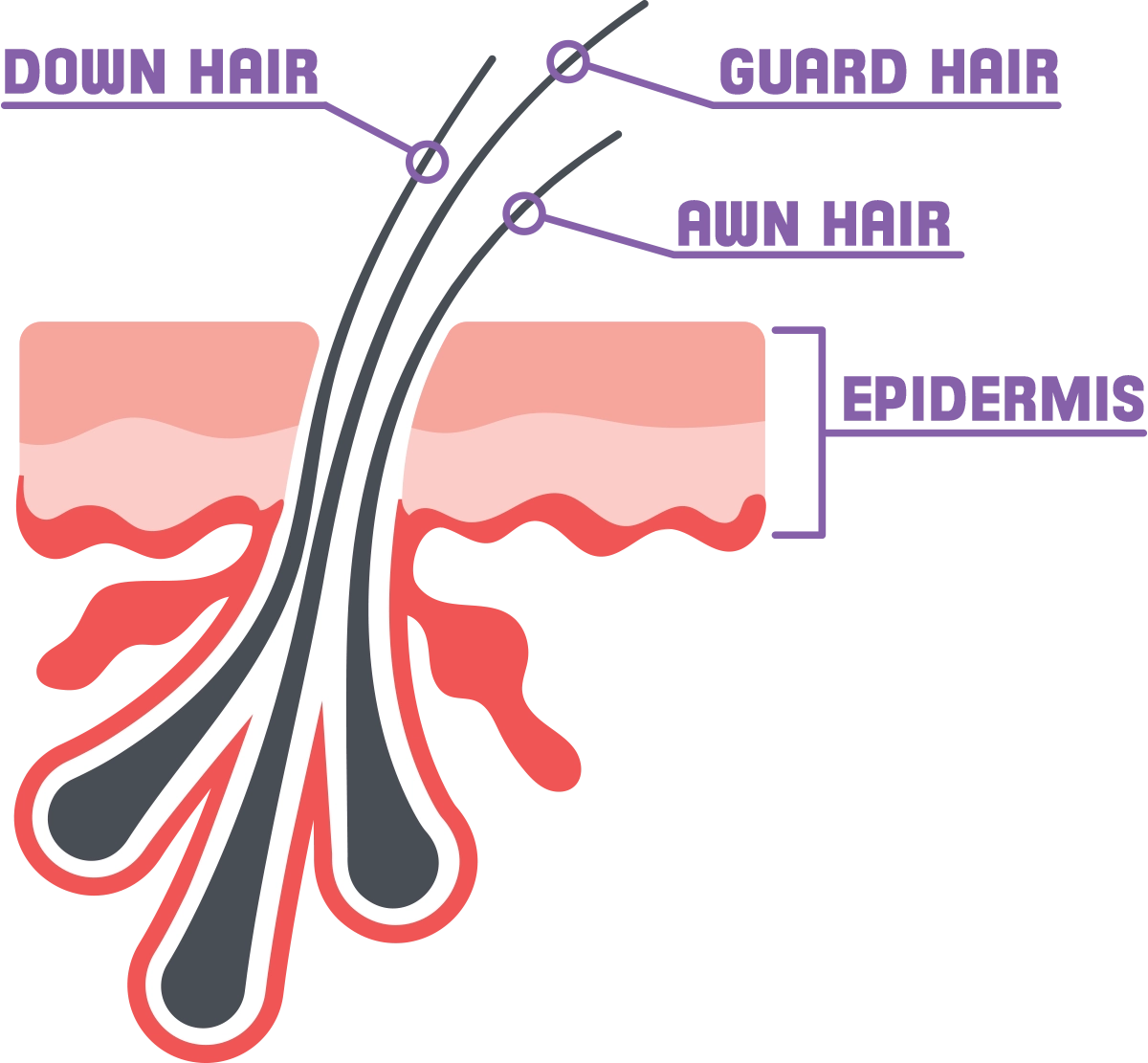

In addition, as with the problematic shaving of fur-type dogs, the wispy and less protective undercoat hairs, which are more prone to matting, grow back quickly and heavier after shaving. The more protective and important primary or guard hairs do not grow back as quickly or as well, especially in older cats or cats that are repeatedly shaved.

The next layer of this debate between the two schools of thought in cat grooming centers around shaving a cat “against the grain.” Cats’ hairs grow to a genetically pre-determined length; that is, they grow to a certain length and stop. In dogs, we call these coat types fur not hair. And as in dogs with fur-type coats, they should not be cut, especially not on the upper torso, unless truly necessary. Most importantly, cats’ fur generally grows—with some breed exceptions—in a direction, from the head towards the tail and from the top of the spine downward.

There are those that aggressively defend—even require—shaving against the direction of the natural lay of a cat’s hair. Having asked about this point of view, the rationale given to me was that it was artistically necessary to smooth out the cut without showing lines. Not surprisingly, this camp also has no problem doing lion cuts or complete shave-downs on the whole torso for reasons no more serious than owner request. A few have told me that full shave-downs are all they do when they groom cats. Every cat, every time. Shaving is cat grooming to them.

Shaving a cat against the direction of the growth of the hair has several potential negative consequences. First, it can tear the delicate arrector pili muscle attached to the hair follicle. The arrector pili muscles function in thermoregulation by lifting the hair to make space for a layer of heat when the weather is cool or lying flat when the weather is warm. They are also important for giving social signals (i.e., raising their “hackles,” which is called piloerection). Shaving a cat against the hair growth can pull and stretch the arrector pili muscle and damage it.2

The argument also comes from the pro-shaving camp that cats are cooler and more comfortable if shaved. But, that is not a fact-based conclusion since cats do not have sweat glands that cool their skin. Cats have apocrine glands that hydrate inside the follicle, not exocrine glands, as humans do, which deliver hydration directly to the skin surface to cool it.

A final argument in contradiction of shaving against the natural lay of a cat’s coat has to do with the health of their hair follicles. Clipping a cat’s hair with a short blade against the grain pulls it the opposite direction from which it grows, causing the hair to pull away from the follicle and the way it normally lays. This leaves the hairs shorter than the level of the skin, causing the hair root to retreat inside the follicle below the skin level.

We should always make our grooming decisions based on what is best for the cat. And it is the highest calling for us to make those decisions based on facts, science and published data where possible. We would all benefit from getting more data about the consequences of some of our grooming decisions. Until then, common sense and a love for these naturally beautiful cats will hopefully guide us to not destroy, but instead protect, their natural and abundant fur coats.

- Trotman TK, Mauldin E, Hoffmann V, et. al., (2007, October 18). Skin fragility syndrome in a cat with feline infectious peritonitis and hepatic lipidosis. Vet Dermatol. 18(5):365-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2007.00613.x. PMID: 17845626; PMCID: PMC7169342

- The Certified Cat Groomer. (2021). International Professional Groomers, Inc. and Professional Cat Groomers Association. Linda Easton, ICMG, Kim Raisanen, CMCG